In defence of creative play and wizard wheezes

Pirates at Blood and Thunder 4 (2018). Credit: Rob Grayston)

Written by Rob Grayston, the designer for Collegium, an online megagame about running a magical university. Here Rob puts forward his defence of wizard wheezes and why they are required in megagames.

Oscar Wild had a line for practically everything, and I can’t help but think of this one when I think about wizard wheezes:

“Anyone who lives within their means suffers from a lack of imagination” (1)

The megagame experience is often a balanced mixture of three core aspects. Some games have more or fewer of these aspects, but these are commonly present in varying doses:

Resource Management + Negotiation + Creativity = Fun (2)

Here I’m going to look at creativity (a.k.a wizard wheezes), and why it’s good for megagaming. This isn’t an instruction manual for creative play, but don’t worry – there may be a future article to help with that.

The Big Points (or “Why Are They Good?”)

Big Point #1: Wizard wheezes and creative play can help players have a better time

Wizard wheezes are a useful tool in megagames which help supplement game mechanics, allowing players to craft strategies and problem-solve beyond the scope of the rule-as-written, and are a useful way to give players agency. Everyone likes to be able to see the effects of their actions in a game, and players having a good experience is what megagames are all about.

If you want players to care about the megagame, let them have the option to get creative (even if they choose not to).

Big Point #2: Game mechanics cannot handle everything

No designer could possibly account for the full breadth of human creativity, and even if they could just think of how long it would take to develop a game that did this, or the sheer size of the rulebook that would be needed.

As an aside, history and media are littered with times people acted outside of conventional rules, with varying degrees of success. I’m sure you can think of some yourself, but the Trojan Horse, Hannibal crossing the Alps to invade Italy, and Sun Bin’s “missing stoves” ploys all come to mind.

Big Point #3: Sometimes they’re needed to keep a game going

This is also important to bear in mind when considering that many megagames, owing to their scale, are effectively playtests. A lot of games (war, board, roleplaying, etc.) get playtested many, many times, which is something that is pretty hard to replicate for an entire megagame. Even those which have been played several times sometimes need control intervention to smooth out rough gameplay, or shift things around when a player or team ends up in a situation without much agency.

In the heat of a game mechanics may break, rules can get missed, and before you know it parts are falling off and patches may need to be applied - good use of wizard wheezes can help with this and save people from having a bad experience.

So we should just make stuff up willy-nilly?

No, silly goose.

Not at all!

If you’re familiar with roleplaying games, none of this should be new to you - think about how a Games Master helps guide you through schemes and plans which aren’t always covered by the game’s rules.

Wizard wheezes are very similar. They are guided creativity which fits the megagame’s tone and expectations, sometimes going around, but also in between existing game mechanics. The aim isn’t to unbalance things, play a “winning move”, or cause an unnecessary headache for the control team.

A criticism of wizard wheezes is how they sometimes feel as though they’re resolved through blind chance because they’re not in the rules. Being a game’s mechanic doesn’t make something better, and it can feel just as “unfair”; there are examples from previously run games of rules killing players on a D6 roll of 4+ with no means of defence, or for an “assassination” card meaning instant-death when given to someone.

It’s not fun to have an assassination card played on you, but more it’s also not terribly fun to play.

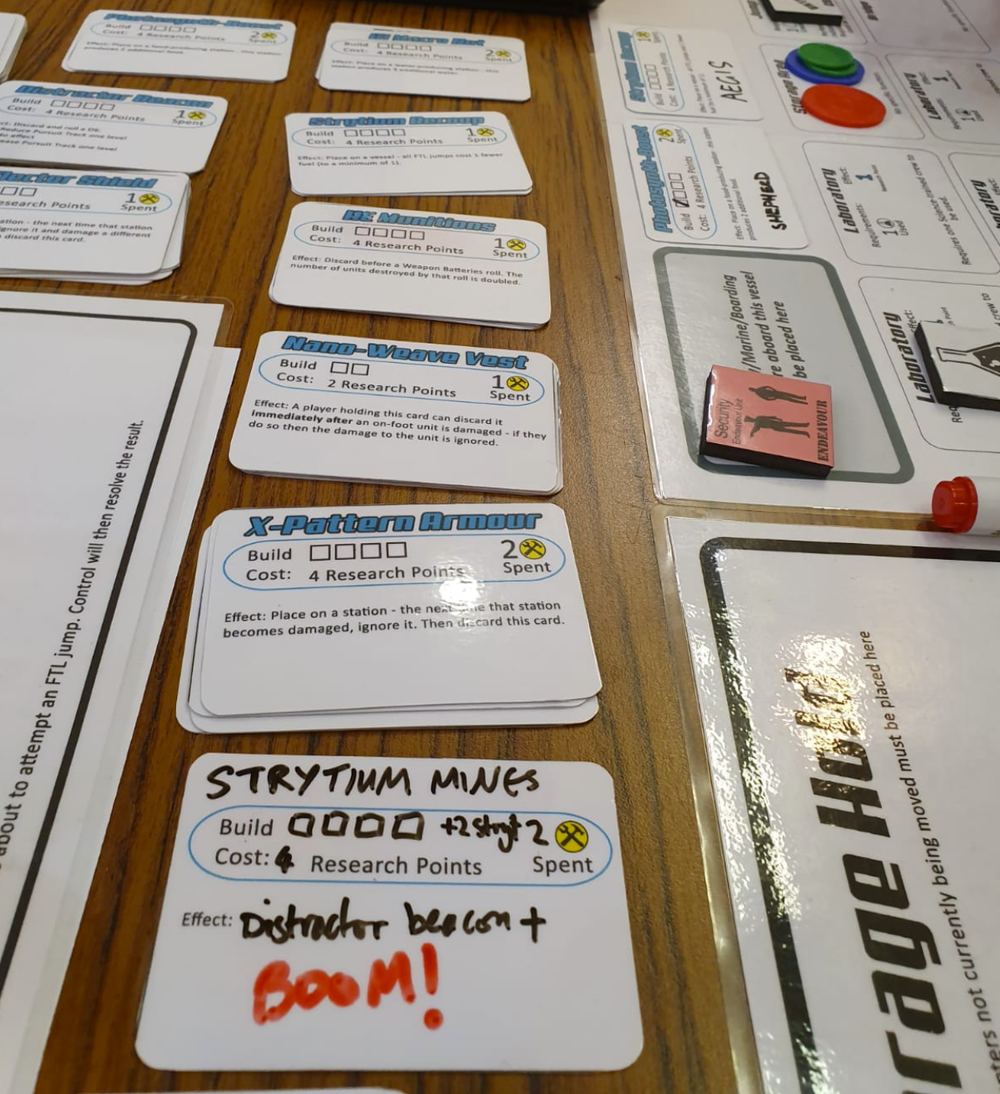

Used well, we all love dice and cards in megagames (long may they reign) but they can also be very useful for creative play; take a look at the tool below, developed by a gaming professional to resolve actions by probability.

It needs two differently-coloured 6-sided dice, and you can input modifiers as necessary. Simple, informative, and its being completely independent of game context means control can easily modify it to facilitate wizard wheezes, amending the probability of success quickly as players collect X, spend Y, and/or perform Z.

Credit: Major Tom Mouat

This is getting a little close to “How to Wizard Wheeze” territory instead of “Why Player Imagination Is A Good Thing”, but it should be clear from the above breakdown that wizard wheezes are so much more than merely hurling control and players headfirst into freeform make-believe. They exist as a complementary tool to enhance the established framework of the game, and can be very satisfying to enact as a player or facilitate as a control.

EXAMPLE:

No matter how devious the plot, in a strictly historical game about dynastic politics, war, and trade in medieval Europe, nobody will be able to summon Cthulhu as part of a plan to depose the Pope.

However, if a team or player(s) in the same medieval Europe game are interested in collecting some exotic wild animals as means to show off to other nobles, that would be appropriate to the game’s tone and has some precedent behind it. Control could calculate how to integrate this plan, perhaps using the game’s trade mechanics and specifying a new trade route needs to be set up with, say, the Venetians or the Byzantines. It could also be that money needs to change hands, or maybe a castle needs to be found to host the new collection - all steps to be trodden to achieve a goal which, in all likelihood, will not be covered by the game’s rules.

The player(s) involved now have more reasons to engage with other players they may not otherwise have talked to, and develop a plan for a cool asset they may feel protective over. When the wizard wheeze is completed it’s not just a Menagerie (+1 Prestige). This is “that time we built a zoo in the Tower of London and Sam fed the rebel leader to her favourite bear so we founded the Order of the Bear and then everyone joined so we declared the Bear Crusade!”

It’s more than a card and a stat, it’s a fun experience that will get talked about for years to come.

(In this hypothetical medieval megagame, a designer might provide control with a selection of historical ‘wheezes’, giving foundations for creative play. In a world where The Cadaver Synod and selling the Papacy actually happened, is a Bear Crusade really that unreasonable?)

Sometimes a Wolf Agent needs to get… creative. Den of Wolves (2019) Credit: Rob Grayston

But in a game with rules, is it fair to make stuff up?

This is down to what you mean by “fair”, which seems to come in two flavours:

A) People having agency and fun

B) “We didn’t know you could do that!”

If someone is having a bad time because of a poor experience entirely within the game’s rules, or they’re new to megagames and not sure what to do, or they’re shy and anxious, fairness will not be fixed by a megagame designer adding another spreadsheet, +1 loyalty card, or a neat way of recording which faction has the most influence.

This can be fixed by a control stepping in and allowing for an alternative avenue of play beyond the scope of the rules, which can help people make an impact on the game and have a positive experience.

When it comes to the second point, this is down to setting expectations for a megagame. You know, before attending the game, that you are not attending a big run-through of Settlers of Catan or Axis and Allies - this is a megagame, and that means a degree of creativity may be present.

You may have received materials like background and rulebooks, as well as personal briefs, which should help inform the tone. If you’re unsure about something, you can always contact the game designer prior to the game, or ask control on the day. Also don’t be afraid to Google the subject matter (or more! I know players who devour relevant books and podcasts for some games), as this can help with setting expectations.

For a bit of context though, Théoden of Rohan probably wasn’t thrilled with Saruman’s wizard wheeze at Helm’s Deep, and the last French invasion of Britain can’t have been too happy with Jemima Nicholas’s creative play either.

But hey! If you do encounter a wizard wheeze and think its addition has been unfair in a world of rules, don’t worry - the Pentagon may be inclined to agree with you.

Wizard wheezes abounded at Dreams of Empire (2015). Credit: Rob Grayston

Conclusion

You might still think wizard wheezes are silly, or another ruder word. You might like certainty and rules so you always know what’s (probably) happening, and game mechanics that provide a decent expectation framework – but without wizard wheezes and creative play, you may as well be playing another all-day diplomacy and conflict driven game like Twilight Imperium.

In the words of Megagame Assembly “… at your next (or first) megagame, have a think about what you could accomplish by working in between the rules.

We think you’ll be pleasantly surprised.”

(it’s what Oscar would have wanted)

(1) it was a quote toss-up between this or Eames’ line from Inception

(2) thanks to Seumas Bates of True North megagames for pinning these ‘megagame pillars’ down

We hope you enjoyed Rob’s thoughts on the subject of wizard wheezes as much as we did. Do you agree or do they just ruin a great megagame experience? Let us know your thoughts on our Facebook group.

We’re always looking out for folks to write for Megagame Assembly, so if you have thoughts on what makes a good megagame, or you think you’ve got an idea that will change the very fabric of time itself, let us know!